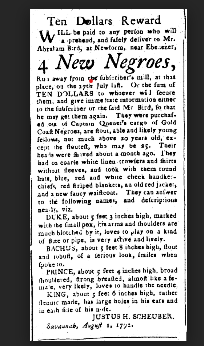

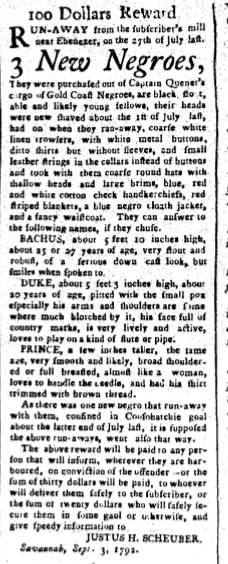

They were far from home and fearful of all. Already one of their number had been captured. As Bachus, Duke, and Prince hid in the swamps and marshes of what is now Jasper County, South Carolina that hot September day in 1792, these bound men knew they did not want to return to a life of slavery. It is not known at this time what became of the three men. Perhaps they were recaptured and returned to their owner, Justus H Scheuber. Maybe they evaded capture and integrated themselves with what became the Gullah community of African slaves in the South Carolina Low Country. But the possibilities of discovering their fates is just one of the reasons why the Augusta-Richmond County Public Library System’s Georgia Heritage Room has started compiling a collection of fugitive slave notices published during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries in the Augusta Chronicle.

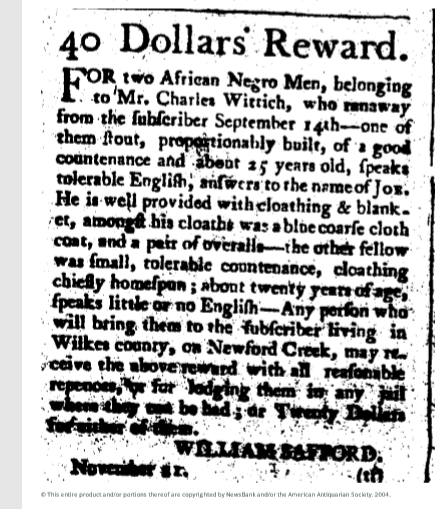

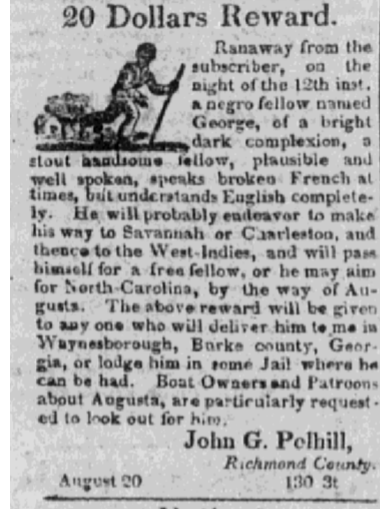

The noble experiment of keeping Georgia free of slave labor ended with a royal decree in 1751 and by the time of the American Revolution, slavery was firmly entrenched as a way of life in the newly formed state. The Augusta Chronicle, long reputed to be one of the oldest running newspapers in the state, carried advertisements of runaway slaves from its earliest days. Descriptions of runways littered the pages of the newspaper, providing a wealth of information on individuals that might otherwise have never been documented. Names, ages, physical descriptions, family relationships, previous owners or places they lived are included to help identify the fugitives, as owners attempted to recover their “property.”

Under the institution of American slavery, enslaved human being, were defined in economic terms, seen as property and sometimes referred to as chattel, necessary to the smooth functioning of the plantation, a system that existed only because of their labor. Nowhere in the equation did humanity enter into the picture. A slave went on the run for myriad reasons, the most obvious being the horrific cruelty inflicted under the system of slavery, but no matter the reason, a fugitive slave was ultimately a financial hit to the slave owner so he or she (in the case of a female slave owner) would stop at nothing to get the slave back. For this reason, the fugitive slave notices that appeared in newspapers all over the county, including papers in the Northeast, were highly descriptive. Ironically, the attention to detail that slave owners hoped would result in the return of their property today has the potential to teach historians more about the lives of slaves, and for African-Americans searching for ancestors, another avenue of inquiry.

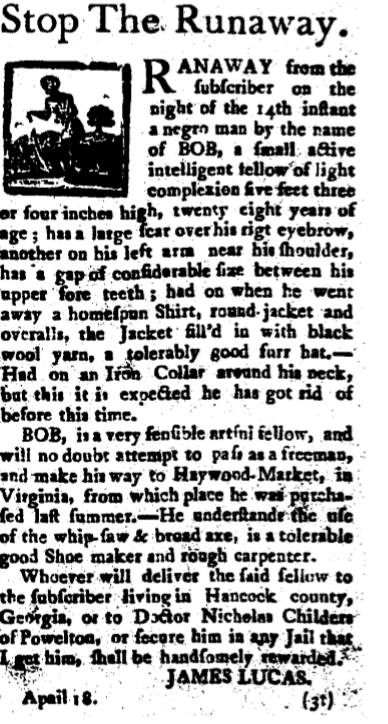

Each runaway notice is a small biography recording the life and humanity of someone who otherwise is lost to history.

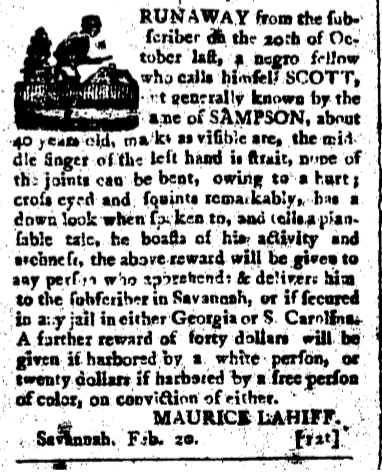

A recurring theme throughout most of the notices is one of brutality, indicated by the physical details slave owners used to describe the fugitive slave. In the advertisement above, Bob is described as having “a large scar over his right eyebrow, another on his left arm near his shoulder.” Most likely these scars are the result of the beatings that were part and parcel of daily life on the plantation. A few lines down we are told that he, “Had on an Iron Collar around his neck.” It is this incessant brutality that motivated many to flee, risking their lives to escape the violence.

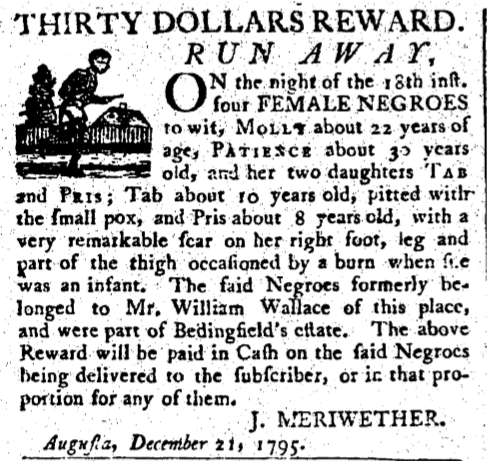

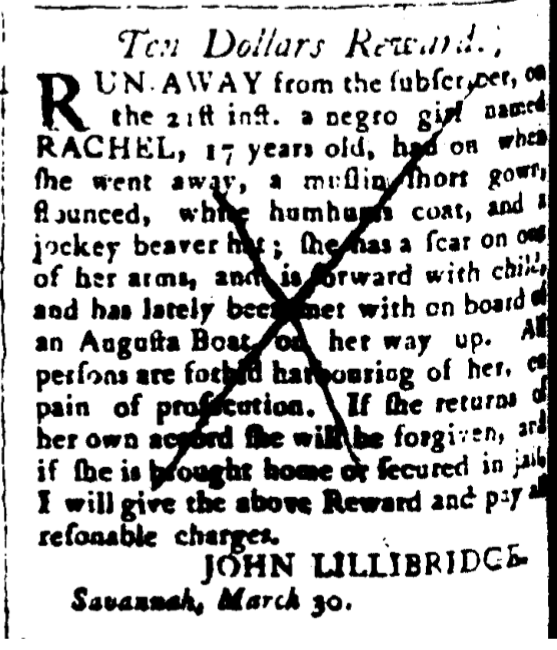

Women too ran away, and children. Many, if not all, of the notices detail the garments the slaves were wearing when they fled, in addition to items they may have carried off. Above we learn that Rachel wore, “a muslin short gown, flounced, white humhums coat, and a jockey beaver hat.” Humhum was a coarse plain cotton cloth, historically used in the making of towels, and imported from India. In the area of textile history, the notices give a fascinating look into the fabrics produced and used during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, providing another useful resource for historians studying this period.

We also read that Rachel was only seventeen, and seemingly alone when she ran, and is “forward with child.” What sort of desperation caused this young woman to run? Was she fleeing an abusive master who raped and assaulted her, leaving her with child, or was she attempting to reunite with the father of the child who was possibly sold off to another plantation. Both are very likely scenarios within the context of slavery. Heartbreakingly, families were routinely separated when slave owners sold off family members to distant plantations; or upon the death of a plantation owner, estates were liquidated and slaves could be portioned off to heirs or sold apart to pay off debts.

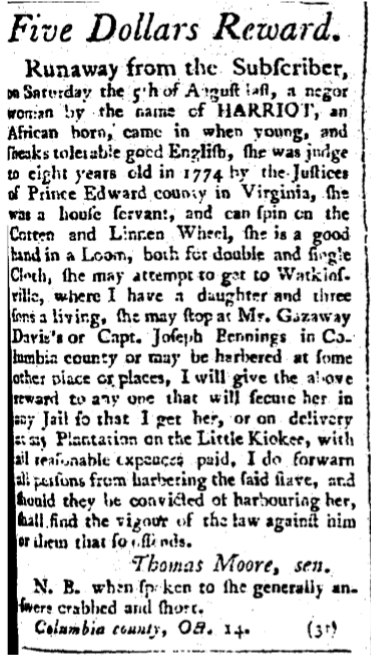

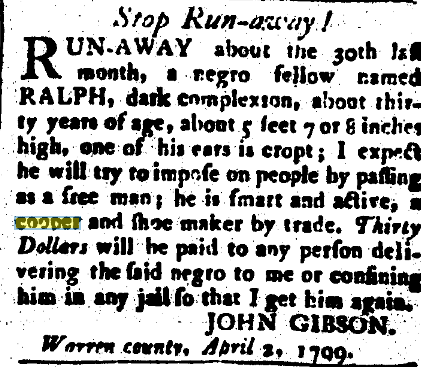

The plantation system was a business enterprise, and many slaves were skilled tradesmen and craftspeople, contributing to the overall success of the plantation. Those who ran off, taking with them a skill or craft integral to the daily machinations of the household were especially sought after. The slave, Harriot “was a house servant and can spin on the Cotton and Linnen Wheel, she is a good hand in a Loom, both for double and single Cloth.” Sometimes slaves with specialty trades, such as blacksmithing or in the case of Ralph, “a cooper and shoemaker,” were hired out to other plantations, giving them an open opportunity to run, which many took advantage of.

These notices are just a few examples of the nearly 750 the Georgia Heritage Room staff has currently amassed dating back to 1786. The scope of the project is expected to run through 1865 when the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified and slavery was officially abolished throughout the United States.

It is estimated that over 200,000 fugitive slave notices appeared in newspapers all over the country from the mid-part of the eighteenth century well into the Civil War. Of these 200,000 notices, nothing else is written about the individual lives of these human beings. In an attempt to bring their stories to light many institutions including the Library of Congress and Cornell University have collected notices and made them accessible to the public. Here are a few more examples from our own collection: