In its inaugural issue dated March 25, 1971, Dr. Mallory Millender’s first editorial introduced the News-Review, as a “brand new newspaper” that would serve the “whole community” but would have “a particular concern for the black community.” The News-Review which became the Augusta-News Review in November of 1972, ran weekly for almost fourteen years and became a voice for Augusta’s African American citizens. At the time of its first issue, almost one year after the Augusta Riots of May 1970, it was among few African American newspapers in the CSRA.

As primary sources, historic newspapers are windows into the social, political, economic, and cultural trends affecting and shaped by local communities during a particular moment in history. They provide context to those of us studying history by giving a 360 degree view of the time period in the communities they are representing. No other primary source has that power. As one of the few Black newspapers in Augusta, the News-Review filled a vacuum in Augusta’s Black community by identifying itself as a “community paper with a predominantly Black readership” that presented the issues of the Central Savannah River Area (CSRA) from a “Black perspective.”

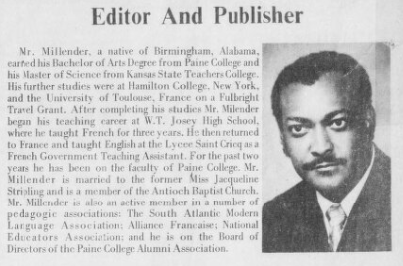

Mallory Millender grew up in New York City but came to Augusta in the 1960s to attend Paine College. Following his undergraduate degree, Dr. Millender received a Master’s in Journalism from Columbia University in New York and a Doctorate from Clark University in the Humanities. He settled in Augusta in the early 1970s, accepting a professorship at his alma mater. As a full-time professor of French and journalism at Paine College, Dr. Millender already had a full plate when he decided to fill the media void in the Black community with a newspaper centered around advocacy and communication. Primarily communication between the white leadership who governed Augusta and their African American constituents. He was seeking transparency and a way to bridge the gap between those making decisions for the city and those affected by the decisions. On page 2 of the March 25, 1971 edition he wrote, “our goal is communication… In order to achieve this goal we plan to feature interviews with persons shaping the destiny of our community.” True to his word future issues would feature interviews with Augusta’s mayors, sheriffs, and leaders of organizations and institutions that directly impacted the citizens of Augusta.

The News-Review began publication almost a year to the day of the May 11-13, 1970 Augusta Civil Rights uprising, using the medium as a sounding board for the century-long struggle of African Americans in Augusta to achieve a quality of life on par with their white neighbors. Dr. Millender was at the rally in front of Augusta City Hall following the gruesome death of sixteen year old Charles Oatman that ultimately sparked the three days of violence. In the end, the city burned, businesses were destroyed, and six Black men were gunned down by police officers. All six men died from gunshot wounds to the back. The suspicious death of Charles Oatman while under arrest at the city jail sparked an inferno in the Black community that had been smoldering for years. Decades of oppression at the hands of white Augusta had finally come to a head. Moving forward, The News-Review positioned itself to address the inequities and injustices plaguing Augusta’s African American populace.

Following the unrest, the National Urban League (Southern Regional Office) conducted a social and economic audit as it related to the Black community of Augusta. The News-Review printed the lengthy final report in a weekly series for several months and included commentary from local Augusta leaders, professionals, business owners, clergy, and more, both Black and white, on why the violence had occurred and what solutions they recommended. The Report concluded that inequities in employment, housing, health, education, welfare, and other areas needed immediate attention and it was “imperative that city government move immediately to correct the long-standing inequities between Blacks and whites in the Augusta community.”

For its almost fifteen year run, the Augusta News-Review never deviated from its original mission to fight for the social and economic equality for Augusta’s African American citizens. The post-civil rights era of the 1970s and 1980s was a pivotal time in the United States and the News-Reviews tackled hard issues, featuring journalists such as Pulitzer Prize winning columnist E.R. Shipp and Michael Thurmond, the chief executive officer for Dekalb County and a former representative in the Georgia Assembly.

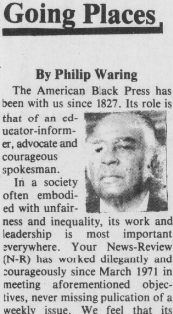

At the forefront of Augusta’s fight for civil rights in the 70s and 80s was J. Philip Waring who worked tirelessly as an advocate for the proper recognition of local African Americans who contributed to Augusta’s history. Earning a Master’s Degree in Social Work in 1947 from Columbia University in New York, Waring returned to Augusta following his retirement from the Urban League in 1977. His work with the Urban League began in 1950 and took him all over the United States, including stints in Harlem, New York and St. Louis, Missouri. Waring also worked in journalism; known for his column “Going Places by Phil Waring” which appeared in several Black newspapers across Georgia, including The Augusta News-Review. The column ran for fifty years and at the time of its publication was the longest running column of its kind in the state.

The top-notch reporting of the Augusta News-Review did not go unnoticed, recognized both at the national and local levels for their efforts. In 1982, Mallory Millender was awarded by the National Newspapers Publishers Association (NNPA) for an editorial he wrote on the care of his son. A few years earlier, J. Philip Waring was awarded the West Augusta Rotary Club’s annual communication’s award for his article “Blacks Who Helped Build Augusta”. In his final article, printed in 1985, Waring wrote of the awards, “These were ‘firsts’ for any Black paper in the CSRA.”

By 1985, the newspapers circulation had grow to about 10,500 subscribers but according to J. Philip Waring had always operated on a shoe string budget. Many of the paper’s contributors were volunteers and interns, including journalism students at Columbia University who Dr. Millender gave writing assignments for experience. Over the years the newspaper never missed a week of publication but often struggled to meet payroll and cover IRS withholding taxes, interest and penalties. The penalties added up, and on a few occasions Dr. Millender took out personal loans to cover the costs. In his final editorial on March 16, 1985, Dr. Millender explained the IRS debt to his readership and commented, “Barring a not necessarily desired miracle, this will be our last issue.” He went on, “After nearly 14 years of ripping and running, working day and night, I am just tired.”

Looking back, Dr. Millender mused, “We believe that we have fulfilled our mission. For 14 years, we have delivered both information and a perspective that our community otherwise would not have had. Editorially, we have provided a voice that otherwise would not have been heard. We have been honest, forthright, and uncompromising in our commitment to truth and justice for all people.”

The loss of the Augusta News-Review was a blow to the CSRA but the spirit of the newspaper lives on in another long-running African American weekly directly inspired by Dr. Millender’s newspaper. Barbara Gordon got her start working for Dr. Millender and through his mentorship and support published her own newspaper in the early 1980s. The County Courier which later evolved into the Metro Courier has been in continuous circulation since, continuing the lineage of great African American newspaper men and women in Augusta.

As we celebrate Black History Month, take a moment to peruse the issues of The Augusta-News Review in the Georgia Historic Newspapers website. The Georgia Heritage Room with permission from publisher, Dr. Mallory Millender, partnered with the Digital Library of Georgia to have the newspaper digitized in 2021. Follow the links below.

https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn88054028/

https://gahistoricnewspapers.galileo.usg.edu/lccn/sn88054027/