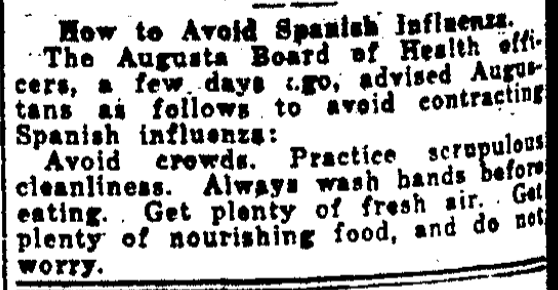

How to Avoid Spanish Influenza

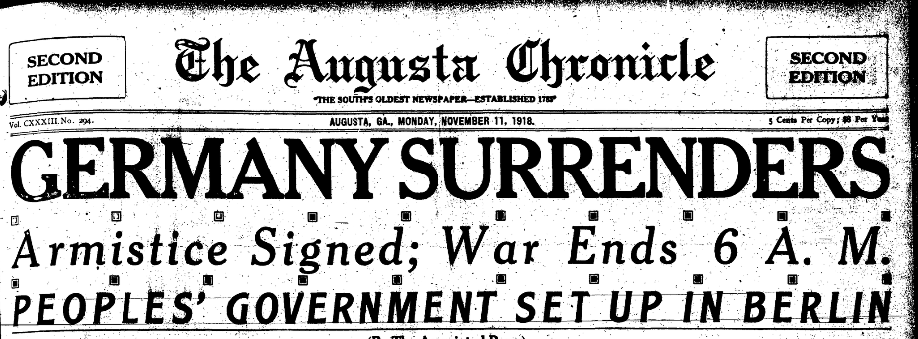

Avoid crowds. Practice scrupulous cleanliness. Always wash hands before eating. Get plenty of fresh air. Get plenty of nourishing food, and do not worry.

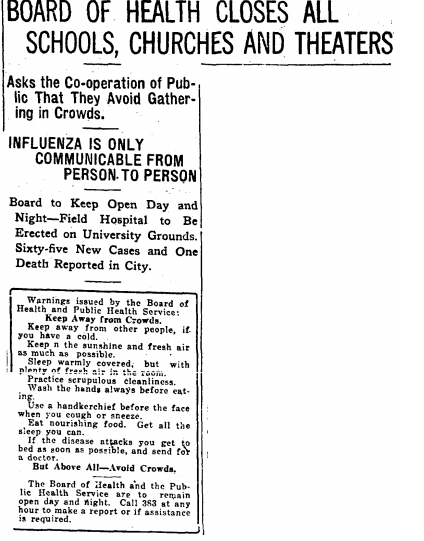

Printed in the Augusta Chronicle a little over 100 years ago, on September 30, 1918, this statement issued by president of the Augusta Board of Health, Dr. John Wright sounds eerily familiar to what we are being told to do today by the Center for Disease Control and the National Institute of Health to limit the spread of COVID-19.

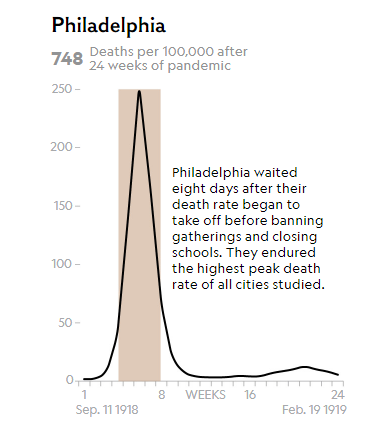

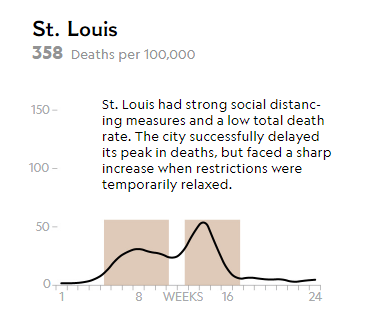

While none of us have lived through a pandemic such as COVID-19, and the world is a much different place than it was at the end of World War I, the Spanish flu does set a precedent for us and offers some guidance on how to proceed. Many studies were conducted following the 1918 Spanish influenza, comparing how major U.S. cities responded, and what measures were taken to limit the spread of the virus. For example, Philadelphia waited longer than most cities to implement social distancing measures, such as closing schools, churches, and banning other social gatherings, and even decided to host a parade that drew a crowd of over 200,000 people. Because of this, the city saw a total of 748 deaths, compared to St. Louis, a city that implemented strict social distancing measures early on in the pandemic, thereby “flattening the curve,” and at 358 deaths, had one of the lowest mortality rates of any major U.S. city.

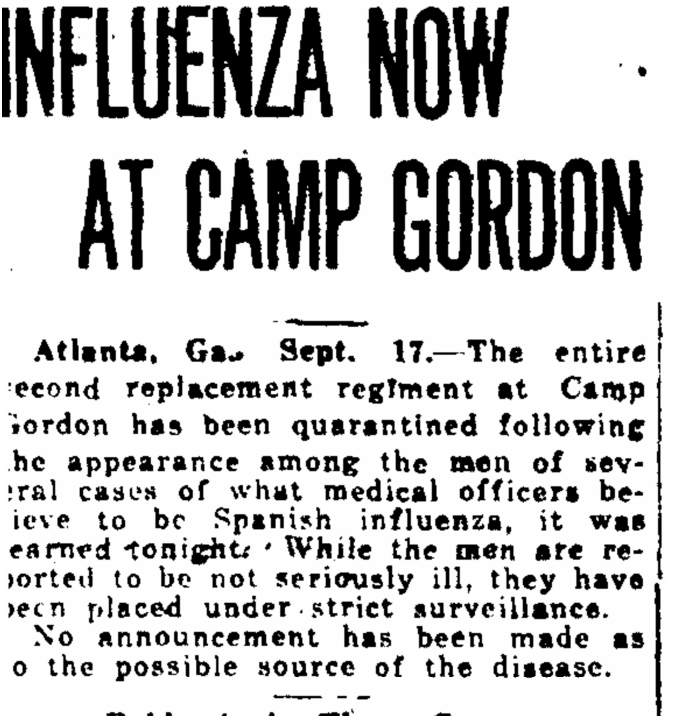

The first known U.S. case of the Spanish influenza occurred at Camp Funston, Kansas in March of 1918, and from there quickly spread across the country. The first cases reported in Georgia occurred at Camp Gordon in Atlanta. A September 17, 1918 article in the Augusta Chronicle stated that the camp had been quarantined in light of the illness, and went on to compare other cases at army camps in Massachusetts, Virginia, and New York where U.S. Army Surgeon General, William Gorgas said the disease was at epidemic levels. Because of the crowded conditions, and the travelling of military officials from camp to camp and across the Atlantic, the virus spread unabated through army and navy installations throughout the United States.

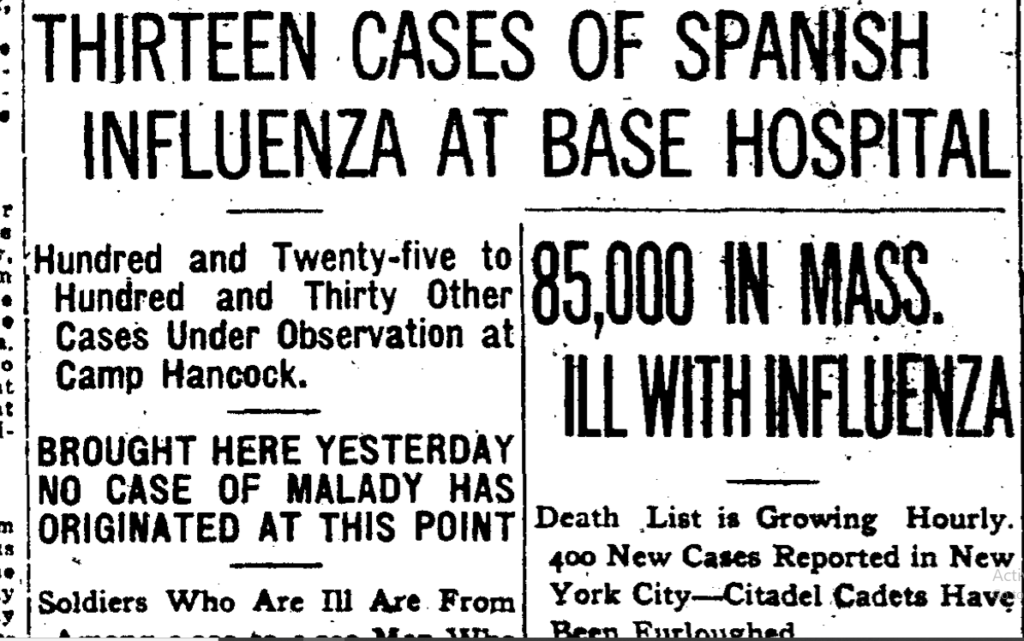

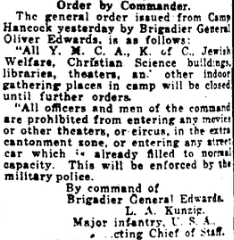

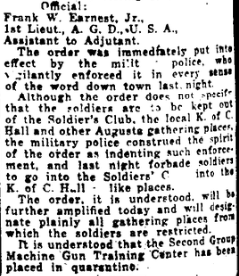

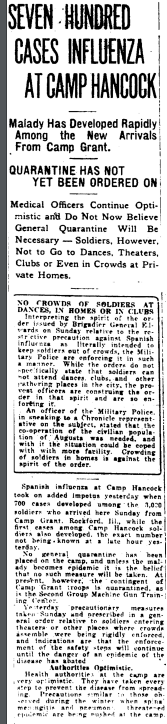

For days afterwards, the Chronicle reported no influenza at Camp Hancock nor in Augusta proper, but it was only a matter of time before cases began popping up, and on September 30, 1918 in bold, block print on the front page, the newspaper reported that 13 out of 3000 troops, recently arrived to Camp Hancock from Camp Grant in Rockford, Illinois were infected with the dreaded flu. Army officials downplayed the cases, insisting that none of the infections originated at the camp, and given the healthy conditions of Camp Hancock compared to other army camps around the United States, they believed “the disease will be controlled at this point without great difficulty.” However, the camp went on immediate lock down, quarantining those sick, and limiting the movement of soldiers within the camp, but stopping short by continuing to allow soldiers to visit downtown Augusta.

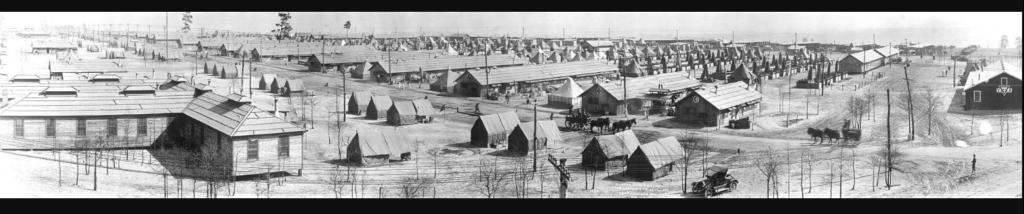

Camp Hancock was a massive World War I temporary military installation named for Civil War General Winfield Scott Hancock. Located on 1,777 acres at the top of “the Hill” where Wrightsboro and Highland Roads converge with Daniel Field, the rising tent city held 35,000 men, and 1,300 buildings, barracks, eating halls, hospitals, showers, latrines, storerooms, garages and office buildings.

The following day on October 1st, the number of reported cases at the camp jumped to 700 and the city’s Board of Health began enacting social distancing measures. Streetcars were ordered to not overcrowd, limiting them to the carrying capacity of seated passengers only and soldiers from the camp were banned from riding any public transport though they could still accept rides in private vehicles. The Board also ordered the newly arrived Ringling Brothers Circus to limit their crowds to 1200 people at a time. Time and again, the disease was downplayed as “not that serious” and as long as people kept themselves clean and well nourished they would have no trouble avoiding the disease or quickly recovering if they did become ill.

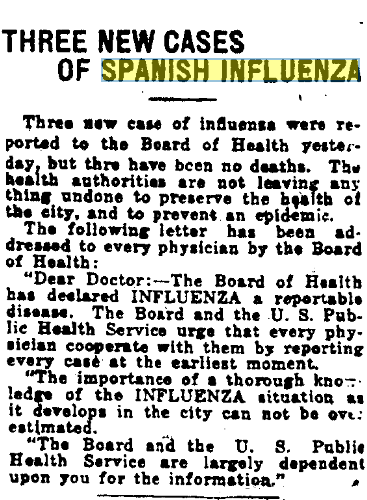

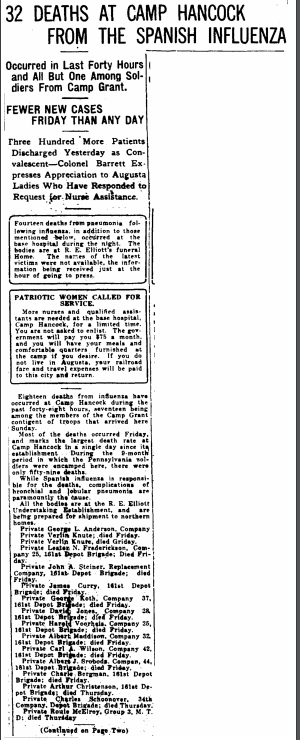

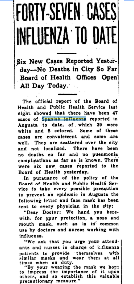

By October 4, 1918 three cases were reported in the city, but two days later on October 6th, the Chronicle reported a total of forty-seven cases scattered around Augusta, including 200 cases in Graniteville and fourteen in Blythe. Area health officials began issuing face masks to local physicians and encouraging them to have their nursing staff wear the same. Travel to Camp Hancock was also prohibited. By October 5th, the Camp had suffered a total of thirty-two deaths since the outbreak began on September 30th with ten of the deaths happening in a forty-eight hour period. Elliott Funeral Home handled the funerals, and the newspaper began listing the dead. Striking are the ages of those who succumbed to the virus. Unlike COVID-19, the Spanish influenza was especially fatal to the young and those with strong immune systems.

On October 7, 1918, Augusta reported sixteen new cases in the city, and twenty-five deaths at Camp Hancock. The following day the newspaper reported a total of sixty-five cases emerging in a twenty-four hour period bringing the total number of to 112. Stating that the numbers in Augusta had not yet reached epidemic levels, but in an effort prevent that from happening, the Board of Health issued an immediate city-wide quarantine – closing schools, churches, movie houses, and banning public gatherings, although “open-air” gatherings for funerals, church services and fairs were still allowed.

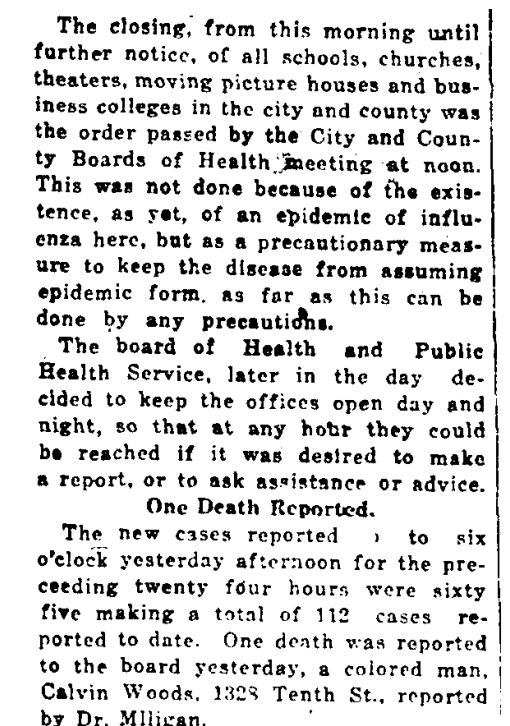

During the month of October 1918, the city of Augusta suffered eighty deaths as a result of the Spanish flu, which the Chronicle reported to be the highest number of deaths to occur during a single month period in the history of Richmond County. However, by the end of the month cases at both Camp Hancock, and in the city had begun to wane, which city health officials attributed to the strict quarantine measure.

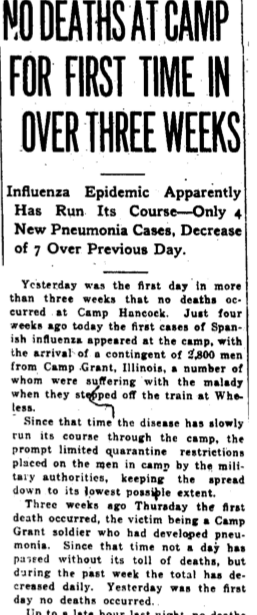

The Armistice was signed on November 11, 1918, ending World War I, and with fewer cases emerging in Augusta, the flu seemed to be losing steam as well. As a result, the Board of Health decided to end the six week quarantine on November 15, 1918.

Almost immediately new cases of Spanish Flu were reported. Schools still reopened and Augusta went back to its normal routine, but by December 17, 1918 it was obvious that the epidemic was not over. On January 9, 1919 the Board of Health once again placed a flu quarantine on the city. Despite the order, several churches reopened to the public “for prayer” only. Advertisements for every tonic and “cure-all” to fight the flu appeared in the paper daily, and had been since the epidemic began. This time the quarantine ban stayed in place until February 1, 1919, although schools remained closed until February 10th. By this time the number of new cases being reported to the Board of Health was dropping significantly and officials were more confident that the pandemic was finally passing.

Ultimately, the 1918 Spanish flu pandemic lasted until 1920, and according to Center for Disease Control estimates the disease infected at least 500 million people worldwide, with about 675,000 occurring in the United States. The worldwide death toll was a least 50 million, but some sources believe it could have been as high as 100 million, making it the deadliest pandemic in modern history.

“Though seriously affected by the Spanish flu epidemic, Georgia escaped the massive numbers of sick and dying counted in other states along the east coast.”1

It seems Augusta too escaped the worst of the pandemic. In late 1918, the Chronicle reported a total of 1,400 cases in the city and 118 deaths, and Camp Hancock had 7,800 cases with 500 deaths.

Let’s hope we fare as well this time around.

- Womack, Todd. “World War I in Georgia.” New Georgia Encyclopedia. 05 November 2018. Web. 07 April 2020.